Knowing, Loving, and Trusting Christ: What “Faith” Means Biblically

ARTICLE • Faith is more than merely knowing Christian facts, having spiritual feelings, or making moral choices. This article considers how three classic triads—the saving-faith triad, the “faculty-psychology” triad, and the transcendentals triad—enhance out our understanding of faith as our whole-person response to God: knowing Christ as truth, delighting in him as beauty, and entrusting ourselves to him as our ultimate good.

Read time: 7 min

We Need a Fuller Vision of “Faith”

In Christian theology and practice, faith is too often trimmed down to the point of caricature. Some conceive of faith primarily as mere adherence to orthodox Christian doctrines. Others see faith mainly as God-ward desires—relational affections. Still others understand faith ultimately in terms of the will—personal commitment expressed through trusting obedience. Yet Scripture presents faith as all of these together: our unified, whole-person response to God by knowing, delighting in, and entrusting ourselves to Christ.

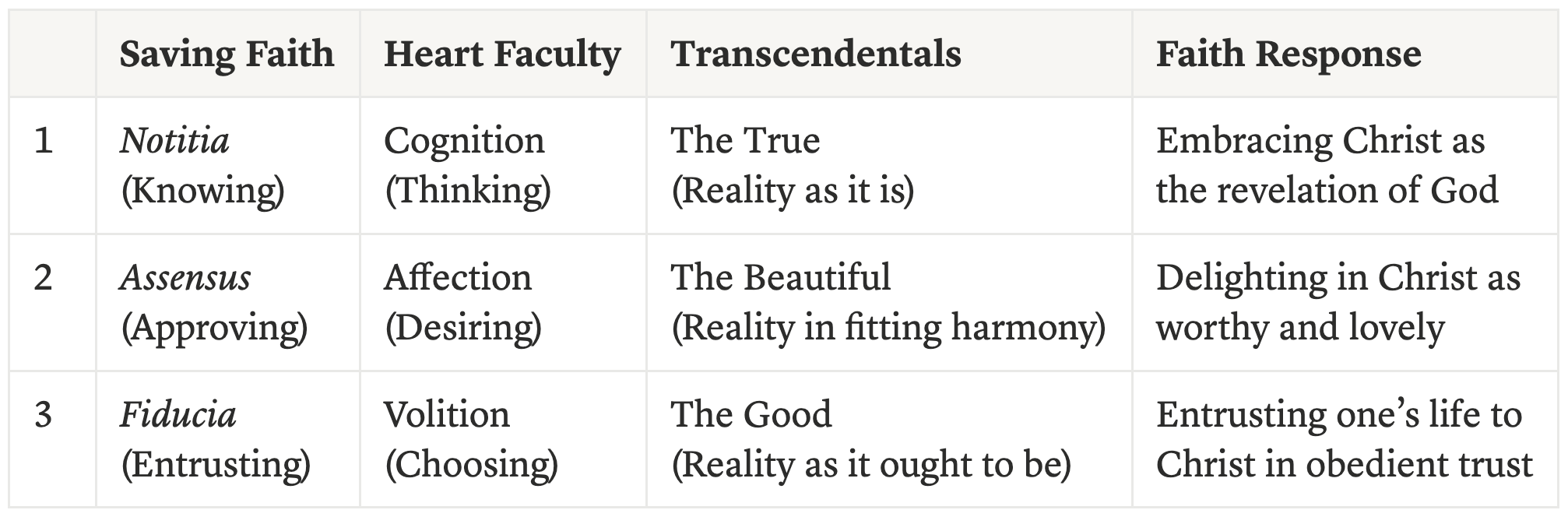

I want to round out our understanding of faith by puttig three well-known philosophical–theological triads in conversation with one another: (1) the Reformation triad of saving faith, (2) the “faculty psychology” triad of human heart functioning, and (3) the famed triad of the classical “transcendentals” or reality. Stay with me—this isn’t mere theological minutia. As I’ll show from the three triads, faith is knowing, approving, and entrusting oneself to God; it’s thinking, desiring, and choosing in accordance with God’s designs for human functioning; and it’s embracing reality in the pursuit of the true, the beautiful, and the good.

1. The Saving Faith Triad: Knowing, Approving, and Entrusting

In Reformed theology, the saving faith triad offers the most direct account of what faith is and does. It involves notitia, assensus, and fiducia. These three Latin words simply describe faith as involving content, agreement/approval, and personal trust.

(1) Notitia names the embrace of divinely revealed content. This is most simply the “information” or truth-claims of the gospel that faith grasps. The gospel is not a bare call to “trust” something vague or mystical. It announces specific realities about who God is, what Christ has done in his life, death, and resurrection, and what God promises in him, among other truths. When Paul says that faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the Word of Christ (Rom 10:17), he affirms that there is something to be heard and understood. When Jesus defines eternal life as knowing the only true God and Jesus Christ whom he has sent (John 17:3), he asserts that God can be truthfully known. Without this knowledge, there is nothing for faith to grasp.

(2) Assensus moves beyond awareness and the belief of truth to inward agreement and approval. Assensus refers to the heart’s judgment that the message of the gospel is true, trustworthy, and worthy of embrace. Scripture consistently locates believing in the heart: one believes with the heart and is justified (Rom 10:10). This is more than cold acknowledgment that certain statements are factually accurate. To believers, Christ is precious and desirable (1 Pet 2:7). If we have faith, we judge that what God says is not only correct, but good and worthy of our allegiance.

(3) Fiducia completes the picture as personal trust and self-commitment. Faith is not exhausted by knowing truths or even agreeing that they are true. Fiducia is the act of casting one’s life on Christ—resting in him, relying on him, and entrusting oneself to his care. Believing in Christ is receiving him (John 1:12). It means living in ongoing reliance. As Paul writes, “I know whom I have believed, and I am convinced that he is able to guard until that day what has been entrusted to me” (2 Tim 1:12). Paul summarizes the life of faith elsewhere when he says that the life he now lives in the flesh he lives by faith in the Son of God (Gal 2:20). Faith, therefore, involves knowing Christ, approving of him as true and worthy, and entrusting outselves to him personally.

2. The Faculty Psychology Triad: Cognition, Affection, and Volition

The second triad stems from a long line of Christian reflection on how the human heart functions. Often called “faculty psychology” in Reformed theology, it simply recognizes that what we do as humans can be grouped into three broad activities: we think, we desire, and we choose. These are often called cognition, affection, and volition.

(1) Cognition refers to how we perceive, interpret, and understand reality. This includes our beliefs, our mental categories, the stories we tell ourselves about the world, and the way we interpret and make sense of our experiences. Our minds are not neutral recording devices. We filter information, connect dots, and draw conclusions. In the realm of faith, cognition includes what we think about God, ourselves, others, and the world—and whether those thoughts line up with God’s revelation.

(2) Affection refers to what we love, value, and fear. Historically, Christian thinkers have used “affections” to describe not just fleeting emotions but the deeper currents of the heart—our settled loves, loyalties, and longings. Two people can know the same facts about Christ; one can remain indifferent, while the other finds Christ beautiful and worthy of devotion. The difference is in the affections. Affection asks: What do I actually want? What do I treasure? What do I dread losing?

(3) Volition refers to what we decide, pursue, and habitually practice. Our wills are not bare, abstract “choosing machines.” What we do flows out of what we believe and what we love. Volition covers our decisions, our commitments, and the patterns of behavior that shape our lives over time. When we speak of obedience, perseverance, or daily choices to honor God, we are speaking about the volitional dimension of our humanity.

Under the noetic effects of sin (that is, the impact of the Fall on our hearts’ functioning), all three are disordered. Apart from the grace of the New Birth/regeneration by God’s Spirit, we do not simply lack information; we inhabit plausibility structures (background assumptions and shared stories that quietly shape what seems believable) that can make unbelief feel natural, and the truth seem improbable. By nature, our minds suppress what is evident about God, our hearts mislabel evil as good, and our wills resist God’s authority (Rom 1:17–30).

Faith engages and reorients all three at once. In salvation, God’s Spirit renews our minds so that we see reality (more and more, though incompletely) as God reveals it. Our hearts are reordered to know savingly what God reveals and love what God loves; our wills are liberated from self-sovereignty and bent toward trusting obedience.

3. The Transcendentals Triad: The True, the Beautiful, and the Good

The third triad focuses not on us, but on the nature of reality itself—what older Christian and philosophical tradition called the “transcendentals.” Wherever there is reality, these three show up in some form. They are the true, the beautiful, and the good. Christian theology has long affirmed that these three are not arbitrary categories; they flow from who God is.

(1) “The true” concerns what is real and reliable. Truth describes reality as it actually is, not as we wish it were. In Scripture, truth is more than just correct information; it is anchored in the character of God, who cannot lie. God’s Word is truth because God himself is faithful and consistent. Christ can say, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life” (John 14:6) because in him, reality is disclosed as it truly is. Faith responds to the true by submitting our thoughts, interpretations, and narratives to God’s revelation.

(2) “The beautiful” relates to what is fitting, harmonious, desirable, and glorious. Beauty is not merely a matter of private taste. At its deepest level, beauty is the shining forth of what is truly lovely. When Scripture speaks of the “beauty of holiness” or the “radiance of the glory of God” (2 Cor 4:6), it portrays God’s character and saving work as compellingly attractive. Christ is true, but he is also captivating. Faith responds to beauty by beholding, delighting, and finding joy in who God is and what he has done.

(3) “The good” speaks of what is morally virtuous, worthy of choosing, and life-giving. Goodness is about what leads to human flourishing under God’s righteous rule. God is good, and everything he commands is an expression of his goodness. Christ is the good shepherd who lays down his life for the sheep (John 10:11). He is the one whose path leads to life. Faith responds to the revelation of God’s goodness (and goodness in creation) by embracing God’s way as the right way and choosing it, even when it is costly.

Scripture presents God as the fountain of all three transcendentals and Christ as their embodied convergence (2 Cor 4:6; Col 2:2–5, 9). Faith more than merely registers that such a one exists. Faith bows to God’s revealed truth in Christ, beholds his beauty, and embraces his goodness as its ultimate good (Ps 34:8). By seeing faith in relation to these three aspects of reality, we discover that believing is a comprehensive reorientation of our entire vision of reality. Faith, therefore, is both responsive and transformative, recalibrating how we interpret what is real, what is worthy of desire, and what is worth living for, based on what God has revealed about himself, ourselves, others, and our world.

Synthesizing the Three Triads

When these three triads are brought into conversation, their inner harmony becomes apparent.

(1) The notitia of faith corresponds to our cognition and aligns with the transcendental of truth. Faith begins as we come to perceive the world and the Christian gospel according to divine revelation rather than personal preference or cultural plausibility. We learn who God is, what he has done in Christ, and what he promises.

(2) Assensus involves the affections and corresponds to the transcendental of beauty. Faith deepens as the heart judges God’s revelation to be not only accurate but compelling, lovely, and worthy of delight. Christ becomes not just “correct,” but precious.

(3) Fiducia entails the exercise of the volition and corresponds to the transcendental of goodness. Faith matures as the will entrusts itself to God in Christ, embracing his way as the only truly good path and expressing that trust in self-commitment and obedience.

None of these lines of reasoning is perfectly clean or chronologically sequential; knowing Christ already involves some measure of delight and self-entrustment. Loving Christ already assumes we know something true about him. Trusting Christ involves both understanding and affection. Yet the categorical correspondences function as a theological map in which faith restores our cognition to truth, our affections to beauty, and our volition to the pursuit of goodness as God has revealed each in his Word.

Implications for Living “By Faith”

Scripture and the Reformation tradition insist that saving faith never exists in only one or two of its aspects. Where faith is genuine, it always involves real notitia, assensus, and fiducia together. One cannot truly know Christ without approving of him, nor sincerely approve of him without entrusting oneself to him.

Yet we believers often grow unevenly in these dimensions. Many of us truly possess all three, yet relate to God in a lopsided way—strong in doctrinal understanding but weak in heartfelt delight, warm in affection but hesitant in obedient trust, or outwardly committed while still shallow in understanding. These triads help us name our imbalances.

Growth in biblical faith, therefore, ordinarily involves the Spirit’s patient work of deepening all three together: clearer understanding of God’s Word (the embrace of truth), richer love for God’s character (the embrace of beauty), and more settled patterns of trusting obedience (the embrace of goodness). Because our growth is grounded in God's gracious work through his Son, the Spirit, the Word, and Christian community, our goal is to more fully participate in knowing, loving, and obeying God based on what he has revealed in his Word.

Based on these three triads, we arrive at a definition of faith:

Faith is the whole person’s response to God in Christ by knowing his truth (notitia/cognition), approving his beauty (assensus/affection), and entrusting/committing oneself to his goodness (fiducia/volition) in lived obedience.

To live by faith, then, is to inhabit reality as one restored by God’s grace in Christ—thinking, desiring, and choosing in ways shaped by God’s truth, drawn by God’s beauty, and directed toward God’s goodness. Now, in dependence on God’s Spirit, let’s make this faith our daily pursuit. ❖

Quote this Article

Footnote: Timothy J. Harris, “Knowing, Loving, Trusting God: How Biblical Faith Involves the Whole Person,” Practical Theologian, December 7, 2025, https://www.practicaltheologian.com/blog/article-z9dtw-69b3c-y384e.

Bibliography: Harris, Timothy J. “Knowing, Loving, Trusting God: How Biblical Faith Involves the Whole Person.” Practical Theologian, December 7, 2025. https://www.practicaltheologian.com/blog/article-z9dtw-69b3c-y384e.